Eye testing and Autism

A young boy wearing headphones.

I seem to have had several conversations across different settings recently about eye testing and autism, so I thought I would put together a blog post on the subject.

When it comes to autism, there is often confusion surrounding language and terminology. Here are some FAQ’s regarding this.

-

This is a really common question and there is no clear answer. With many health conditions we use ‘person first’ language, so we would refer to a person with epilepsy, rather than an epileptic person, or a person with an intellectual disability, rather than an intellectually disabled person. The reasoning behind this, as the phrase suggests, is that they should be recognised as a person first, their disability is not their identity.

When it comes to autism many people, and most importantly those who are Autistic, feel that autism is very much a part of their identity, it is an integral part of who they are and cannot be separated. A majority of the Autistic community have indicated that they would prefer ‘identity first’ language, i.e. we would say an Autistic person, rather than a person with autism; it’s not an add-on, it’s an integral part of who they are.

Even among those who are Autistic, there are varying opinions and viewpoints, so by far the safest strategy is to ask the person themselves, or in the case of those who are non-speaking or minimally verbal, ask those who care for, and support them, what their preference is. For the purpose of the rest of this article, we will use identity first language, since it gets the majority vote from the Autistic community, who are the ones best-placed to make the call.

-

This is a phrase which is still commonly used, however, the preferred term is non-speaking or minimally verbal. The term non-verbal implies a lack of language or communication abilities, and this is not always the case for Autistic individuals, as such, the terms non-speaking or minimally verbal are considered more accurate and also more respectful. A recent journal article argues that we should use the term ‘minimally speaking’, because verbalisations can still be made, but just not as words.

-

While the term Special Needs is still widely used and recognised here in Australia, it is preferable to refer to a person as having disability or a chronic health condition. These terms are likely to better indicate what types of needs a person may have.

Eye testing

Back to the main subject: what about eye tests for Autistic people?

Why have an eye test?

Many families supporting Autistic individuals may be deterred from getting an eye test, because they anticipate that it will be an ordeal for the person themselves and in turn, for themselves, and certainly for some there are significant barriers to undergoing an eye exam. However, evidence from research indicates that Autistic people are at increased risk of refractive errors (short or long sightedness or astigmatism), strabismus (eye turns), and eye movement problems. If refractive errors are not identified and managed with spectacles, they can cause a significant barrier to all learning. Similarly, eye turns benefit from management, which can comprise prescription of glasses, patching, and sometimes an operation to straighten the eye which is turning.

In addition to these eye issues, due to brain-based differences, Autistic people experience the world differently. Having a better understanding of the part that vision may play in a person’s behaviours can be very helpful to families, support workers, educators, and therapists. We will look more closely at these brain-based differences in a future post.

But how?

So, how do we make eye examinations more accessible to Autistic people? Studies are currently underway to better understand how we can remove barriers in eye healthcare. In the meantime, we can learn from consensus opinion of experts. If we examine the guidance from healthcare professionals who frequently work with Autistic people a few themes emerge. Here are ten ways in which we can adjust an eye examination for an autistic person.

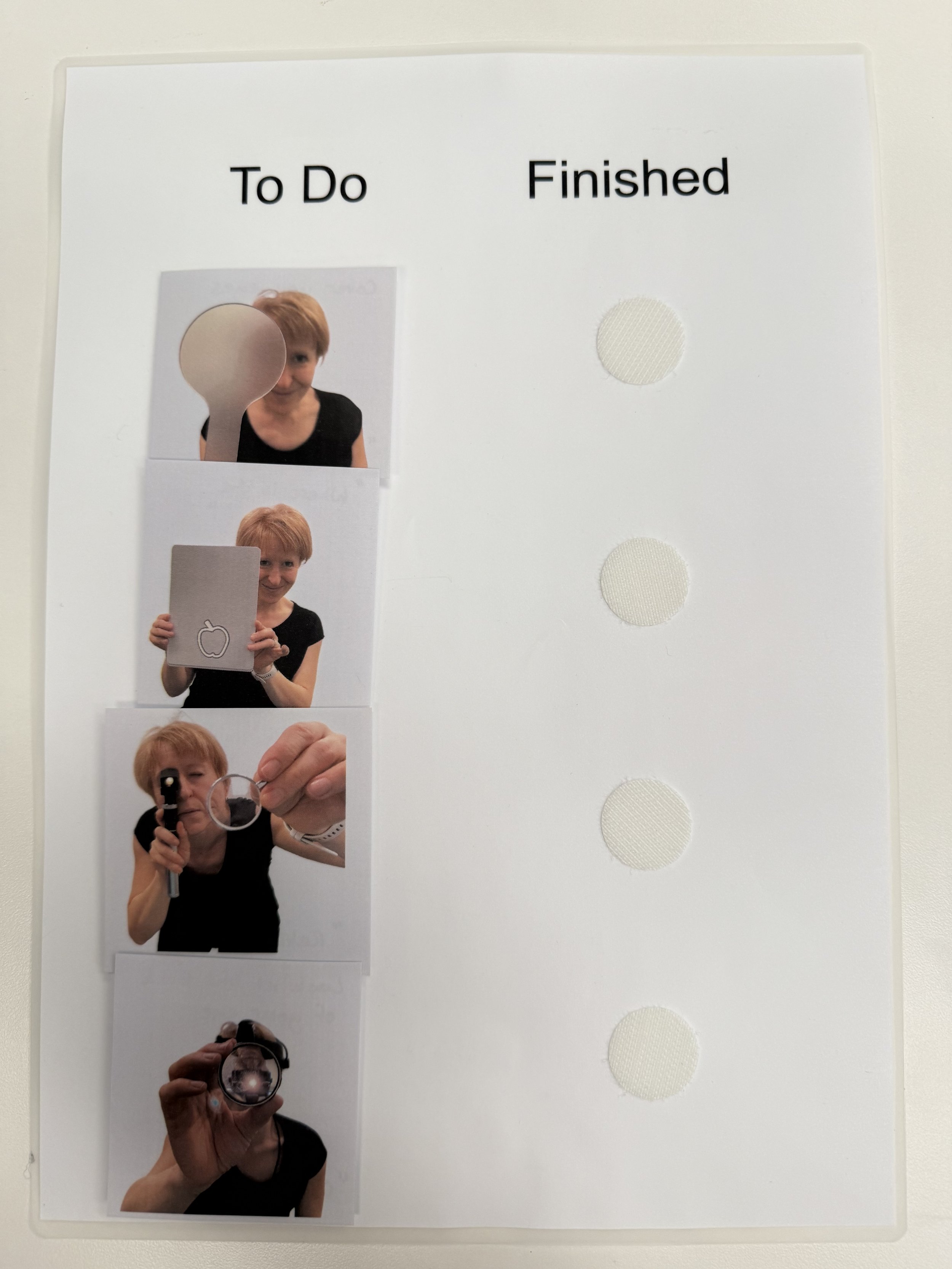

Choice board showing an optometrist performing different assessments from a patient’s viewpoint.

Preparation is important: Many Autistic individuals experience high levels of anxiety, particularly in unfamiliar settings. To help minimise anxiety, families can stop by the practice prior to actually having a vision assessment. This way, they can familiarise themselves with where they are going, and gain a better understanding of what to expect. If helpful, we offer a planning appointment, where a family can book in for a session with the optometrist, but we will just look at the things we are going to use to assess vision, without any requirement for the person to perform the assessment. We can come up with a plan, make up a choice board, and then book in for a separate session to perform the assessments. This can work really well, particularly for children, because they are often a lot more confident the second time they visit, and the opportunity to meet the optometrist prior to undergoing the eye test can really help build rapport.

The option of a social story: At Special Eyes we have social stories available for anyone to use. You can access them via our website. We have a social story for children, and a social story for adults.

A quiet space with low sensory load: For a lot of Autistic people, sensory challenges can be an issue. Places like shopping centres are noisy, and visually busy. Our practice is not located in a centre or shopping precinct, it’s actually rather off the beaten track, down the end of a quiet corridor. We have dimmer switches and blinds to control the lights, and the decor is plain and uncluttered. We have aimed to create a low sensory environment for people to visit. We also acknowledge that the verbal processing abilities of Autistic people varies widely, in view of this, our assessments take longer - we will take the time it takes to successfully complete the eye examination for the person we are caring for.

Preparation continues during the assessment: When testing, I think it’s really important to explain what is going to happen before each test. Next, I always ask the person if they are ready before beginning. This helps them feel in control of the situation, which can further help reduce anxiety. This approach can be really helpful for some Autistic individuals.

Show it first: Autistic people often find it easier to engage in assessments when they have seen them demonstrated. A companion, support worker, Mum, Dad, a sibling, or even a teddy or a doll can help with this by letting the optometrist perform the assessment on them, so the Autistic person can see what is going to happen.

Flexibility and finding different ways: There may be a specific part of the assessment that is particularly difficult for a person. For example, often Autistic children and some adults struggle with wearing the trial frame glasses - the ones we use to hold the lenses. If this is the case, we can skip the glasses and simply hold the lenses up in front of the person’s eyes. Small changes like this can make a big difference.

Fidget toys and home comforts: Bringing in a favourite toy or sensory fidget can be another way to help manage anxiety. People are welcome to bring along whatever they want, including snacks, to help make the vision assessment a more comfortable experience.

Offering breaks when needed: Acknowledging the fact that the whole experience can be quite overwhelming, children and some adults have limited attention spans, and many Autistic people have sensory differences, offering movement breaks can also help. Sometimes you just need to get up out of the chair and move around to stay regulated, and that’s totally fine.

Make it manageable: Even with the above adjustments, the entire experience can be very overwhelming for some individuals on the autism spectrum and sometimes it is helpful to break the task down, performing the various assessments over several visits, rather than all at once.

Objective assessment: The standard approach to assessing visual acuity is to ask someone to read lines of letters on a chart, but obviously this is not possible if someone is non-speaking. We can still assess visual acuity however, through the use of objective assessments such as preferential looking tests, where we use a person’s eye gaze to determine if they can see the target we are presenting. Cardiff cards is an example of a commonly used preferential looking test.

Special Eyes waiting area: a quiet, low sensory space.

Ask an expert

Above all else, we need to keep in mind that no two Autistic people are alike, and what helps one person may not be helpful to another. By far the most important advice when supporting Autistic people to access eye health care would be to ask them what would help, allow time and flexibility for them to communicate using whatever method they prefer, and where there are significant communication barriers, ask the people who support them and know them best. This is the surest way to make eye health and vision assessments accessible.

Interested in learning more?

If you would like to book in, or would like to discuss what an eye examination might look like for an Autistic child or adult, then please reach out. We are always happy to make any adjustments we can to make our eye exams as accessible and comfortable as possible and we acknowledge that you know best how to do that.

Our practice is located in Enoggera, on the Northside of Brisbane. You can call us, send us an email, or book in for an initial free chat with Dr Ursula.